SolarWinds / SUNBURST: Supply-Chain Compromise

A deep dive into one of the most important cyberattacks of the 21st century

👋 Welcome to all our new readers!

If you’re new here, ThreatLink explores monthly how modern attacks exploit technologies like LLMs, third-party cyber risks, and supply chain dependencies. You can browse all our past articles here (Uber Breach and MFA Fatigue, XZ Utils: Infiltrating Open Source Through Social Engineering)

Please support this monthly newsletter by sharing it with your colleagues or liking it (tap on the 💙).

Etienne

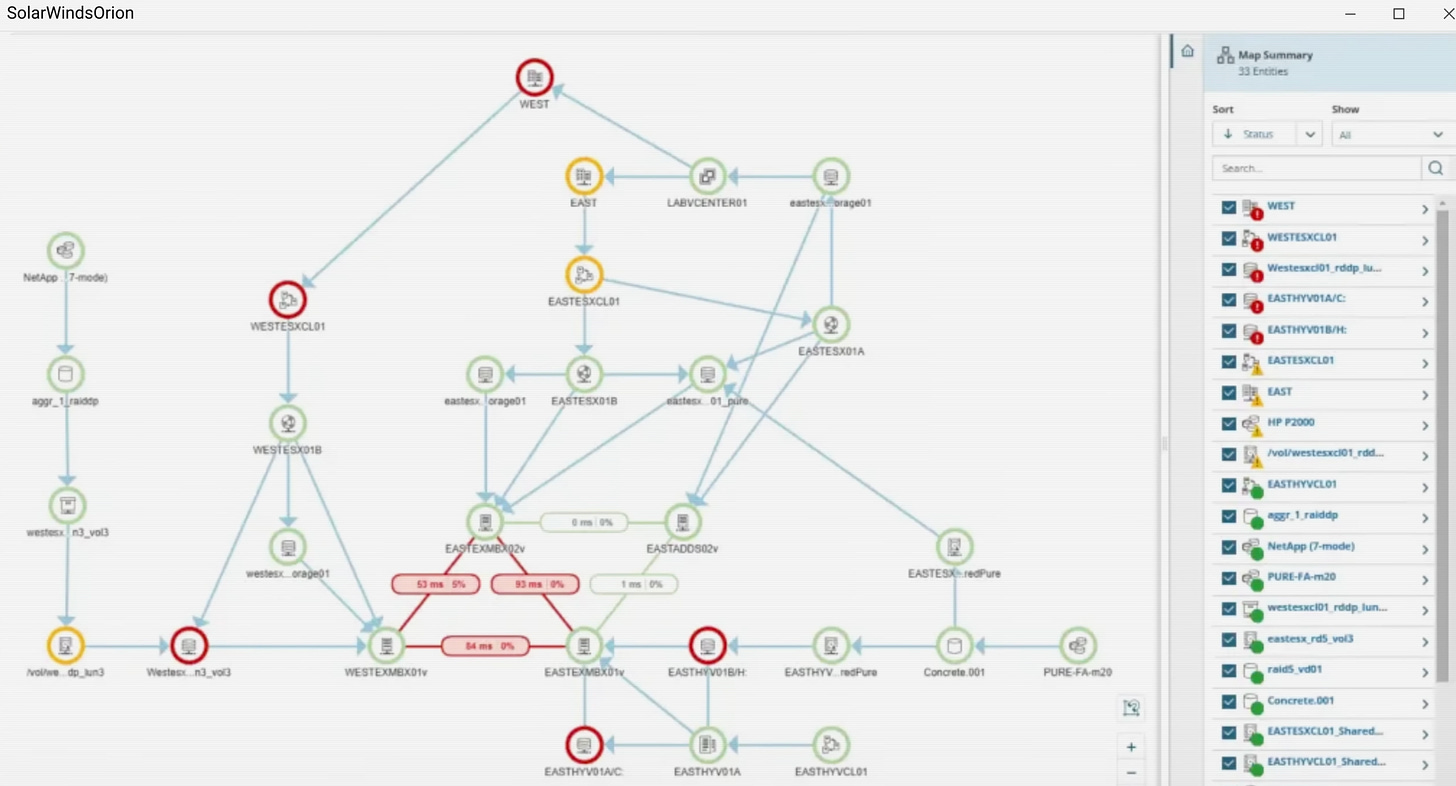

SolarWinds’ SUNBURST incident is the supply-chain breach that permanently changed how security teams think about “trusted” software. In late 2020, attackers quietly inserted a backdoor into SolarWinds Orion, a widely deployed IT monitoring platform used to manage networks, servers, and cloud resources. The result wasn’t a loud smash-and-grab. It was a patient, engineered compromise of the update mechanism itself: organizations installed the malware because it arrived as a legitimate vendor update.

What made SUNBURST so dangerous is exactly what makes modern enterprises efficient: central tooling, broad visibility, and privileged integrations. Orion often sat close to the heart of operations, with deep credentials, federated access, and pathways into identity systems and cloud environments. Once the trojanized update landed, the backdoor enabled selective follow-on exploitation; only a small subset of victims were escalated further, making detection harder and response slower.

This article breaks down how the compromise unfolded

For our next article, I’m thrilled to welcome Tim Brown, SolarWinds’ CISO, whom I had the chance to interview.

Before the Attack

Orion is a monitoring and management platform from SolarWinds commonly deployed with elevated permissions and wide network reach. In many environments it can query Active Directory, poll network devices, reach servers across segments, and store credentials or API tokens for integration. That combination: high privilege, high connectivity, and high trust, makes monitoring infrastructure a high-leverage place to insert malicious code.

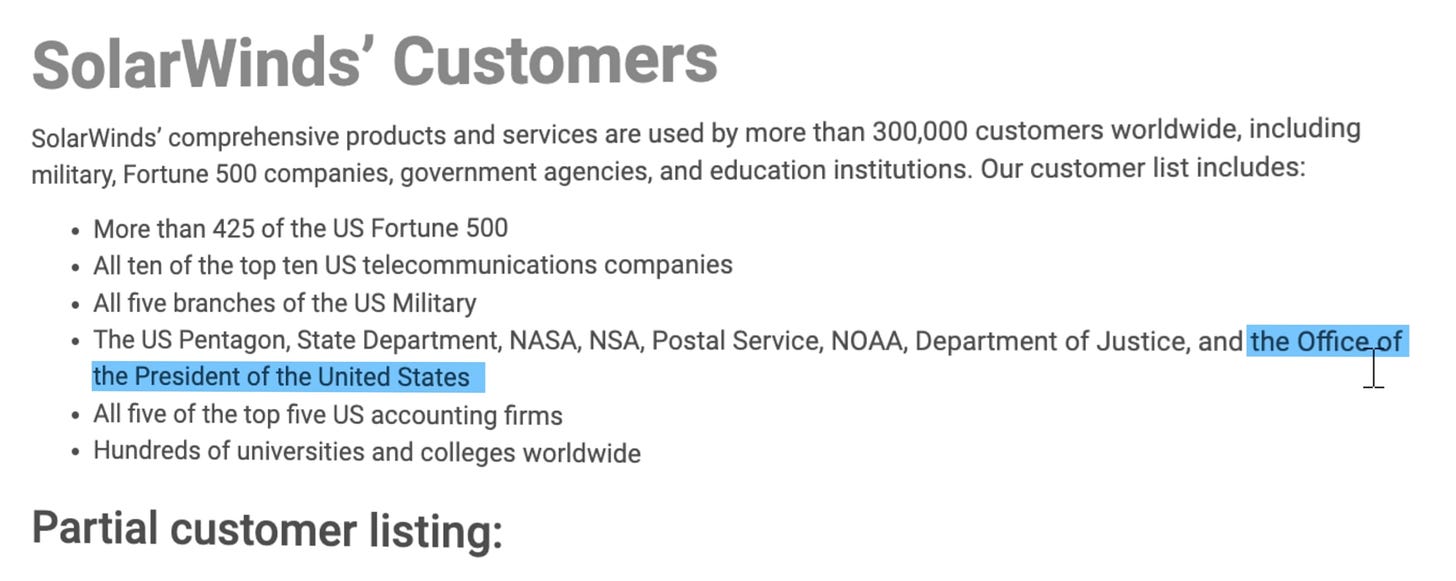

SolarWinds’ customers

In SolarWinds’ own customer materials, the company positioned itself as broadly embedded across enterprise and government IT. Those materials stated that SolarWinds products and services were used by more than 300,000 customers worldwide, spanning military, Fortune 500 companies, government agencies, and education.

A highlighted customer breakdown included:

• More than 425 of the US Fortune 500

• All ten of the top ten US telecommunications companies

• All five branches of the US Military, The US Pentagon, State Department, NASA, NSA, Postal Service, NOAA, Department of Justice, and the Office of the President of the United States

• All five of the top five US accounting firms

• Hundreds of universities and colleges worldwide

This is marketing language, not an incident scope statement, but it helps explain why a compromise in a monitoring vendor’s update channel was treated as a national and ecosystem-level event.

Beginning of the Attack

Late 2019–early 2020: Attackers gained and maintained access inside SolarWinds’ environment long enough to position themselves in the Orion build pipeline.

SolarWinds Orion isn’t a SaaS service where the vendor “pushes” changes inside their own cloud environment. It was classic on-prem enterprise software: you install it in your own network (typically on Windows servers), you run it with your own credentials and integrations, and you periodically download and apply updates yourself.

How the update was weaponized

The model is:

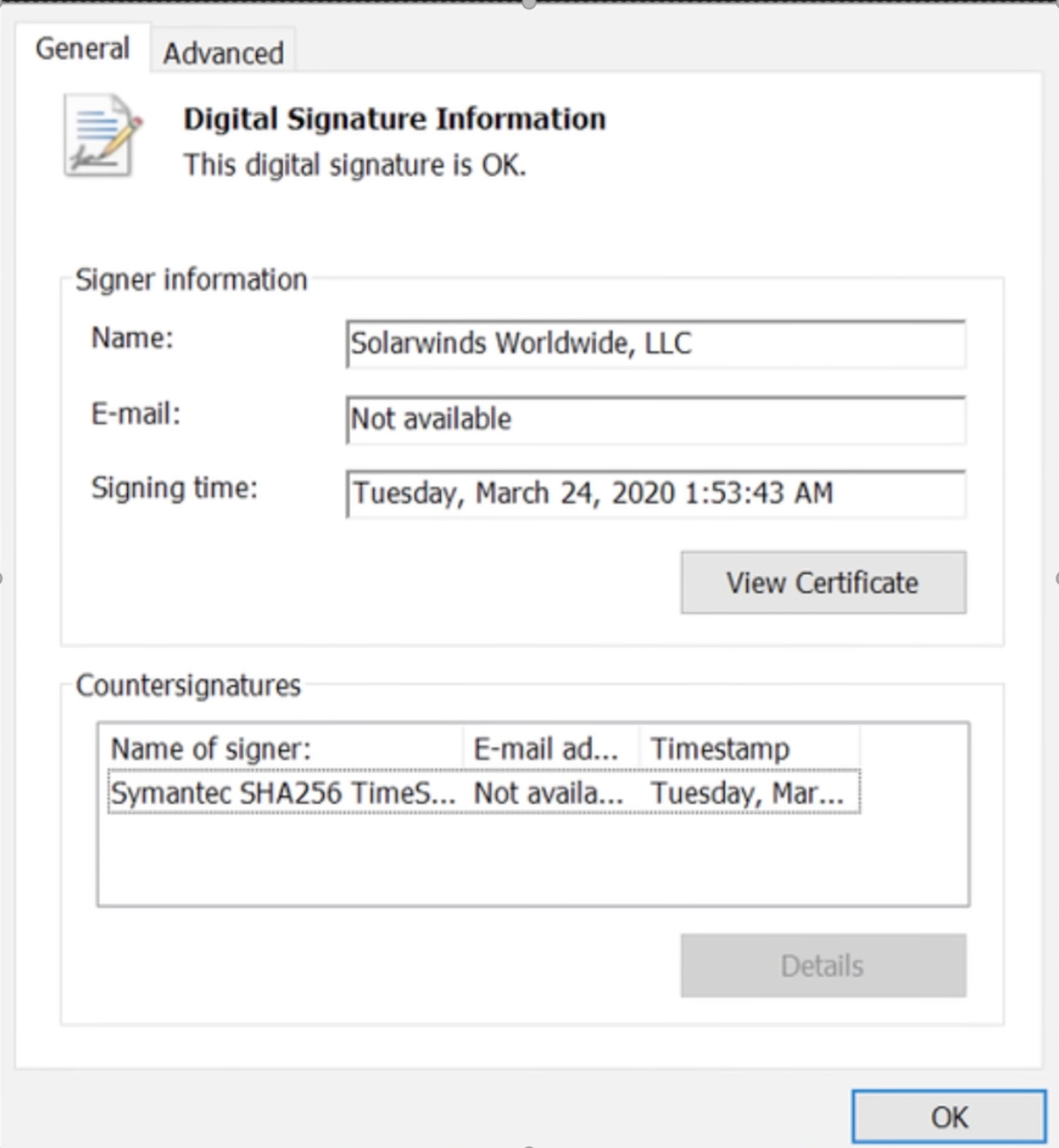

The build process produced a legitimate Orion DLL during compilation (a new legitimate version of Orion)

The injector detected that moment, swapped the legitimate artifact for a trojanized version containing the SUNBURST backdoor, and allowed the build to proceed.

Because the resulting update was produced by the normal build system, it was then digitally signed and distributed through the standard update mechanism.

That distinction matters: it’s not just “malware in an update.” It was malware produced by the vendor’s own build-and-sign pipeline, which meant it bypassed many antivirus/EDR controls (trusted signatures, allowlists, and assumptions about update provenance).

Timeline

March–June 2020: Trojanized Orion updates were distributed (the supply-chain distribution window highlighted in many advisories and incident writeups).

Dec 8, 2020: FireEye publicly disclosed it had been breached and that certain Red Team tools were stolen. During that investigation, FireEye identified a backdoored SolarWinds Orion component as part of the intrusion chain.

Dec 11–12, 2020: FireEye’s investigation converged on the supply-chain mechanism and it notified SolarWinds that Orion updates were compromised.

Dec 7–8, 2020: In parallel with early response activity, SolarWinds’ board appointed Sudhakar Ramakrishna as CEO effective January 4, 2021, replacing Kevin Thompson (who resigned from the board effective Dec 31, 2020).

Dec 13, 2020: Public disclosure period begins; CISA issues Emergency Directive. DLA Piper (law firm) was brought in to manage the incident response team, with CrowdStrike helping for the forensic investigation

Dec 18–24, 2020: Major technical writeups land (Microsoft and FireEye/Mandiant published early deep dives that helped defenders scope IOCs and understand SUNBURST behavior).

Jan 4, 2021: Sudhakar Ramakrishna becomes CEO during the active remediation and trust-rebuild phase.

Jan 2021: SolarWinds brought in external help, KPMG for forensics and a consulting firm co-founded by Chris Krebs and Alex Stamos.

Apr 15, 2021: UK/US attribution to Russia’s SVR is made public in official statements/advisories.

May 12, 2021: Executive Order 14028 is issued, directly pushing software supply-chain security reforms across the U.S. federal ecosystem.

Jul 19, 2021: SolarWinds completed the spin-off of its MSP business as N-able.

Nov 2022: SolarWinds agreed to pay $26M to settle a shareholder lawsuit related to the incident (securities class action settlement reporting).

Oct 30, 2023: The SEC charged SolarWinds and its security executive Tim Brown, alleging fraud and internal control failures tied to cybersecurity risk representations.

Apr 16, 2025: SolarWinds closed its acquisition by Turn/River Capital (taking the company private).

Nov 20, 2025: The SEC dismissed the enforcement action with prejudice.

How the Supply-Chain Backdoor Worked

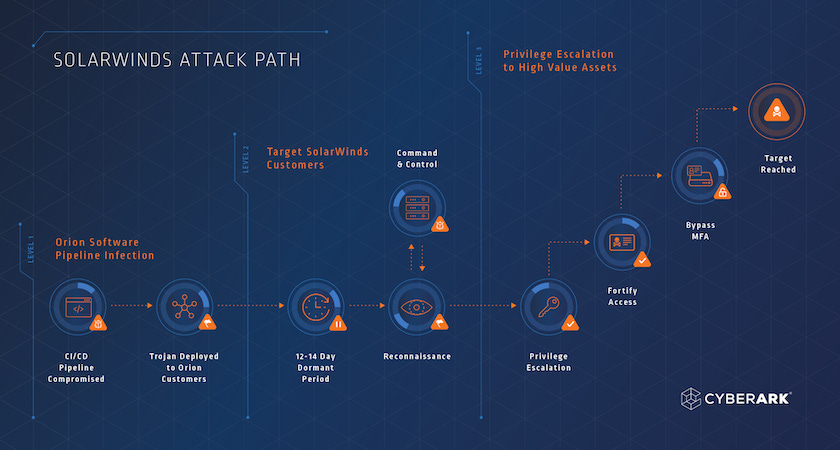

A typical “activated target” path looked like this:

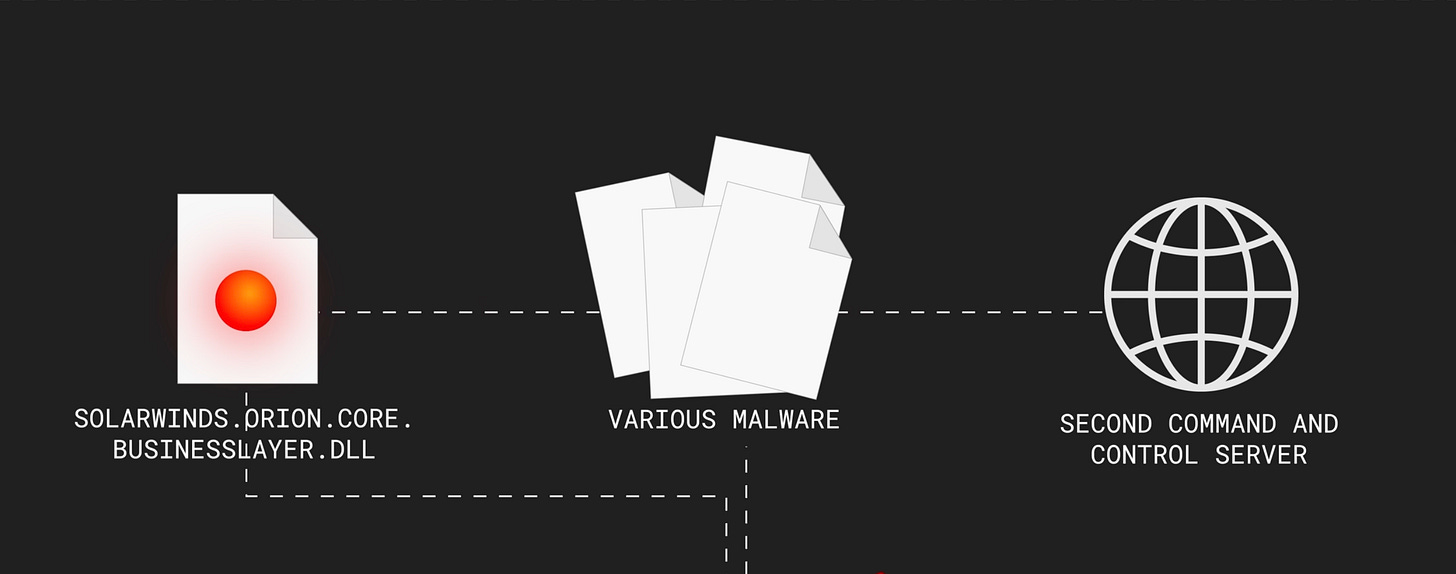

Installation via routine update: The compromised Orion update installs the trojanized SolarWinds.Orion.Core.BusinessLayer.dll.

Dormancy and environment checks: The backdoor waits and then performs checks to reduce noisy execution, while learning about the host and its domain context.

Initial beacon to attacker infrastructure: The malware begins communicating outward (often via HTTP) using domains and subdomains designed to resemble benign cloud traffic.

Victim profiling and selection: Early beacons include metadata (domain and host identifiers, IP ranges, running processes, and Orion configuration). This profiling step helps operators decide whether to invest additional effort.

Tasking from C2: For selected environments, the operator returns commands that use the Orion process context to run reconnaissance and stage next steps.

Delivery of second-stage tooling: The Orion host is used to fetch or drop additional malware (often described as “second stage”), and communications may shift to a separate command-and-control server.

Lateral movement and identity access: Operators pivot from the Orion server into Active Directory and federation/SSO infrastructure, pursuing credentials, tokens, and privileged access. In cloud-connected environments, this is often the bridge from on-prem to M365/Azure resources.

Persistence and cleanup: The operation prioritizes durable access (new credentials, service accounts, remote implants) while reducing forensic signals (selective deployment, timed execution, and opportunistic log/telemetry disruption).

The key point is that Orion was not only the initial access mechanism; it was also a convenient launch point. It already had broad network reach, and activity originating from monitoring infrastructure can receive less scrutiny than user endpoints.

Consequences for SolarWinds

Operational and remediation costs

SolarWinds disclosed cyber incident costs across investigations, remediation, professional services, and customer support, often presented net of expected/received insurance reimbursements in SEC filings.

Legal, regulatory, and disclosure consequences

Beyond the SEC matter (filed 2023, dismissed 2025), SolarWinds also faced private litigation, including the $26M securities class action settlement reported in 2022.

Business and ownership trajectory

The company executed major corporate moves in the years after: the N-able spin-off (July 2021) and later a take-private acquisition by Turn/River Capital (closed April 2025). While these aren’t solely because of SUNBURST, they are part of the longer-term reshaping of the business environment SolarWinds operated in post-incident.

Consequences for Everyone Else

CISA’s emergency directive and subsequent advisories provided a centralized playbook for detection and containment, reflecting how unusual the event was in scope and severity for federal networks.

Supply-chain security stopped being a best practice and became policy.

ISO/IEC 27001:2022 introduced new controls that explicitly address supplier and third-party risk.

Attribution and geopolitics

Public attribution to Russia’s SVR by the US/UK (and partners) reinforced that SUNBURST was treated primarily as a strategic espionage campaign rather than conventional financially motivated cybercrime.

For our next article, I’m thrilled to welcome Tim Brown, SolarWinds’ CISO, whom I had the chance to interview.

Source

Exclusive Interview with Tim Brown and Etienne (Galink)